11 May 1918 -|- Camille Fily[]

Source: The Bike Comes First

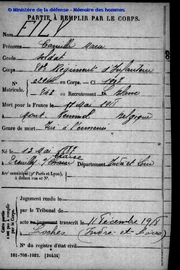

Mémoire des Hommes

Cemetery Loches

Trophy Camille Fily

Camille Fily – The youngest Tour de France rider who was killed on the Kemmelberg[]

By Graham Healy

In June 2013 nineteen-year-old Dutch cyclist Danny van Poppel became the youngest cyclist to take part in the Tour de France since the Second World War. In doing so, van Poppel helped bring attention to the youngest-ever Tour entrant, Camille Fily, who had taken part in the most controversial Tour ever, in 1904.

Fily, who was dubbed “The Lochois Kid” by journalists, was just seventeen years and fifty days old when he took to the start line that year. He took the record from another seventeen-year-old, Jean-Baptiste Zimmermann, who had taken part in the very first Tour. At the opposite end of the scale, there was also a fifty-year-old taking part, Henri Paret. A decade after his debut Tour appearance, Fily would also see action in the First World War.

Fily was born on May 13, 1887, in the small village of Preuilly sur-Claise, south of Tours, in the Indre-et-Loire department. His start in cycling came when he joined his local club, the SV Lochoise. Despite his record-breaking feat of being the youngest Tour rider, he wasn’t the most famous cyclist from his village. Léon Georget, “The Father of the Bol d’Or,” also came from there. Georget earned his moniker from winning the famous Parisian track race nine times, in addition to winning Bordeaux–Paris twice. Léon’s younger brother Émile also won Bordeaux–Paris as well as nine stages of the Tour de France. Both brothers would survive the war.

Fily quickly made an impression on the bike. He was enthralled by the reports from the first-ever Tour in 1903, and vowed that he would also take part in the race. His opportunity came the very next year, when his entry was one of those accepted by the organizers.

Eighty-eight riders lined up at the start of the second Tour on July 2, but this number would be quickly cut down: Thirty-three of the riders pulled out on the first stage, from Montgeron to Lyon. Fily was among those who managed to survive that first stage. He avoided any trouble on the second stage when supporters of local rider Antoine Fauré, who was from Lyon, attacked many of his rivals. The Italian rider Giovanni Gerbi was particularly badly beaten, having been knocked unconscious and suffering a broken finger. He was forced to abandon.

On the third stage, from Marseille to Toulouse, Fily finished sixth, twenty-five minutes behind Hippolyte Aucouturier, and had another top-ten finish on the penultimate stage from Bordeaux to Nantes. Now he wasn’t just surviving; he was showing that he was worthy of his place alongside the older, more experienced riders. There was more trouble on that second-last stage, with nails being thrown on the road, and more scuffles involving supporters. Shots had to be fired at Nîmes to disperse one mob. Numerous riders were also being disqualified by Desgrange after stages for various infringements. Riders were accused of getting lifts in cars and taking illegal feeds. In addition, there were instances of bikes being sabotaged. The race had become a farce.

On the last stage of 462 kilometres from Nantes to Paris, Fily tried a daring attempt to win the stage. He broke away in darkness at Saumur, not far from his home village of Preuilly-sur-Claise. By Tours his lead was up to seventeen minutes and by Amboise—twenty-five kilometers later—it was up to twenty-five minutes. At the halfway point, though, he really started to struggle and was caught by Blois.

Fily did go on to finish the stage, albeit four hours behind. This result left him in ninth place overall in Paris, fifteen and a half hours behind the victor, Maurice Garin. However, the win left a bad taste. Such was the amount of cheating and violence during the Tour that Desgrange considered pulling the plug on the race. He published an article in L’Auto the following day titled “The End”:

“The Tour de France has just finished and its second edition will, I fear, be the last. It will have died of its own success, of the blind passions which have been unleashed, of the abuse and the suspicions that have come from ignorant and ill-mentioned people.”

Desgrange would soon have a change of heart on the future of the race, however, saying that he had “decided the show would go on, once more as a moral crusade for the sport of cycling.”

With his winnings from the race, Garin bought a petrol station shortly after the end of the Tour. However, he didn’t have much time to bask in the glory of his win. In November of that year the UVF decided to launch an investigation into the result. Complaints had been received from a number of cyclists about the amount of cheating that had taken place. During the race nine riders had been disqualified for using cars and trains.

The UVF listened to testimony from many competitors, and after considering all the evidence released their findings on December 2. They had decided to disqualify all of the top four finishers—Maurice Garin, Lucien Pothier, César Garin, and Hippolyte Aucouturier. This meant that Fily had now moved up to fifth place overall.

Unfortunately further investigations took place, and other riders would be disqualified, including Fily. In total, twenty-nine riders were ousted, but the reasons were in most cases never made clear. Some of the punishments dished out were severe. Lucien Pothier, who had originally finished second, was banned for life; the original race winner, Maurice Garin, was banned for two years. His crime was to accept food outside the official feeding zone.

Henri Cornet was awarded the victory four months after the race finished; like Fily, he was still just a teenager. Just shy of his twentieth birthday, Cornet remains the youngest winner of the race. Apparently even he had cheated during the race, getting a lift in a car at one stage.

Fily was suspended for a while, but he would return in time for the 1905 Tour in good form. Just prior to the start of the race, he had a good result when he was tenth in Bordeaux–Paris, won by another of the suspended riders, Hippolyte Aucouturier.

Fily’s main motivation for the 1905 Tour was to make amends for the previous year’s disqualification, and clear his name. Despite being still only eighteen years old, he put in an incredible performance.

Racing for the Guerin Cycles team, Fily had three top-ten stage placings, and finished in fourteenth place overall; Louis Trousselier took the victory. It was to be Fily’s last appearance in the race. Despite showing such great potential, he retired from cycling at the end of the year. His reasons are unknown.

Little would be heard of Fily until the following decade when war broke out. He had signed up to fight in 1915, and was assigned to the Eightieth Infantry Regiment. This regiment fought with great distinction at Ypres in 1914, and at Champagne and Verdun in the following years. In 1918 they would face the Germans again near Ypres.

In April of that year General Ludendorff drew up plans for the Germans to retake Ypres. The plan, known as Operation Georgette, had the objective of driving the British forces back to the English Channel ports and forcing them out of the war.

After four years of fighting, many of the troops on the Allied side were war-weary and low on morale. The initial attacks by the Germans as part of the operation would see a number of British and Portuguese divisions collapsing.

On April 17 the First Battle of the Kemmel took place. Here the German Fourth Army tried to take over the strategically important Kemmelberg but was repulsed by the British. However, there was a very real danger that the Germans would capture it if there was another offensive.

The Kemmelberg was important for both sides: At 156 meters in elevation, it overlooked much of the area surrounding Ypres. The same week that the British repulsed the Germans, Marshal Foch agreed to send French troops including Fily’s Eightieth Infantry Regiment to the Lys sector, where the hill was situated. After the initial British defense of the Kemmelberg, it was agreed that the rested French troops would relieve the British of the position.

On April 25 the Germans attacked again, and this time they were successful in capturing the Kemmelberg. Fighting would continue in the area until the end of July, and casualties would mount for both sides. Two weeks after the Germans had captured the hill, on May 11, Fily was carrying a message by bike at Millekruis, just to the north of the Kemmelberg, when he was shot. He died instantly, just two days before his thirty-first birthday.

Every year thousands of fans converge on the Kemmelberg to witness the riders tackle the climb used in Ghent–Wevelgem, and it is the main focal point of the race. Ghent–Wevelgem was first organized in 1934 as a race for amateurs, and would only have a professional version after the Second World War. On the climb, the cyclists race past Le Mont-Kemmel French Military Cemetery. There is also an eighteen-meter-high statue commemorating the sacrifice, the Monument aux Soldats Français. The cemetery contains the bodies of 5,237 unknown French soldiers and 57 whom the authorities did manage to identify.

Fighting would continue in the area, and the Kemmelberg was retaken by British, French, and American troops in September. The death toll in the area would continue to rise throughout the year. The number buried in the cemetery on the Kemmelberg is but a drop in the ocean compared with the number that died in the Battle of the Lys. An estimated thirty thousand French soldiers were killed along with eighty-six thousand German and eighty-two thousand British.

The sacrifice of the Allied soldiers had made a difference, though: The Battle of the Lys would cause considerable damage to the German army and mark the beginning of the end of the war.

It would have been some consolation to Fily’s family that his body could be identified. His body wasn’t interred on the Kemmelberg, but instead was returned to his family, and he would be buried at the military cemetery in Loches, just south of Tours, near where he had been born.

In addition to being honoured for the sacrifice he made in the war, Fily will also be forever remembered for his cycling achievements. His record of being the youngest-ever Tour entrant is one that will probably stand the test of time.

- For results in the Tour de France, see Tourstats.dk...